My story begins with the voices of those who came before me, echoing across time.

My Korean parents carried both the wounds and the wisdom of a divided homeland. My father, a retired engineering professor at Ewha University, shared a reflection on our family’s story — spanning across the Japanese occupation, liberation, war, loss, rebuilding, and hope.

When I read his letter, I was reminded that who I am is deeply connected to the courage, kindness, and endurance of generations before me. This is how Korean Mama’s Heart Record begins: by remembering.

From My Father’s Letter (abridged)

“Your grandfather was born in 1919, just after the March 1st Movement for Korean independence. His father — your great-grandfather — joined the crowds shouting ‘Mansei!’ at the marketplace. But during the Japanese occupation, people were told to keep such acts quiet, so this story lived only in whispers within the family.

Your great-grandfather’s name was Lee Seung-man — written in the same Chinese characters as President Syngman Rhee. Our family, too, belongs to the same Yangnyeong-gun branch of the Jeonju Lee clan, making us distant relatives. Family stories say that President Rhee’s father once borrowed money from your great-grandfather and never repaid it.

Though the family wasn’t wealthy, your great-grandmother, Jo Ryeong, was strong and frugal. She managed to buy land and made the household more stable.

Your grandfather attended one of the most prestigious schools of his time — Haeju High Ordinary School (Haeju Gobo) — when only 0.045% of students in Korea advanced that far. He loved science, photography, bicycling, and even ice-skating across frozen lakes with a long pole tied around his waist — so he could climb out if he fell through the ice. Once, he traveled to Japan on a school trip and visited Nikko, where he saw the famous Three Wise Monkeys carved at the Toshogu Shrine.

He had hoped to study abroad, but his older brother squandered the family’s fortune through gambling and drinking. So instead, he stayed behind and worked for a farmers’ cooperative in Baekcheon, a small town known for its hot springs.

After liberation in 1945, Soviet troops entered the North. The new Communist authorities confiscated your great-grandfather’s land, and he was later interrogated by local security forces. Your grandfather escaped by jumping out of a second-story window—the power went out, and he fled in the darkness as gunshots followed him.

In 1948, carrying only a blanket, he crossed the 38th parallel into South Korea. He found work at the Nonghyup (farmers’ cooperative) in Deokjeong, Gyeonggi Province. Because he spoke some English, he often sang songs like ‘Swanee River’ and ‘My Old Kentucky Home’ with American soldiers.

Your great-grandfather, devastated after losing everything to the Communists, ended his own life. Every year afterward, our family held memorial rites for him. Because no one knew what became of your great-grandmother in the North, your grandfather’s older brother would visit fortune-tellers each year to ask whether she was still alive.

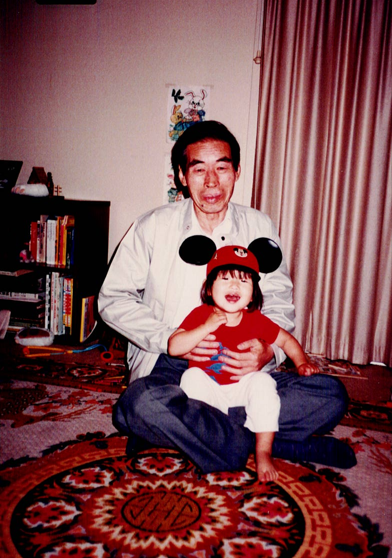

Your grandfather loved American movies, baseball, and quiet family life. I remember watching High Noon with him at Seoul’s Civic Hall and eating galbitang afterward. He was gentle, humorous, and never spoke harshly to anyone. He valued knowledge, science, and music — and taught me, when I was a child, that heat transfers through conduction, convection, and radiation.

He lived through colonization, war, and displacement, yet never grew bitter. He passed away in 2004 at age 85 — a man who endured history with quiet strength. Through his story, we can see how Korea’s modern history wasn’t just written in textbooks, but lived out in ordinary families — in courage, in loss, and in the will to begin again.”

(Written by my father, Lee Byung-Uk. Edited by my mother, Park Kyung-Hee, and translated by Su Yeon Lee-Tauler.)

Korean Mama’s Reflection

Remembering my roots gives me a deeper understanding of the generational influences I carry — and how much healing is much needed from the history of accomplishments, loss, and unfulfilled dreams.

My grandfather, Lee Do-Soo, was a man of few words, but every now and then he cracked ridiculous jokes and shared riddles that made me think. Now that I’m older, I can’t imagine how much trauma he must have endured — experiencing the division of Korea, losing his own father to suicide, leaving his first family in North Korea, and starting over in the South.

As painful as these stories are, I believe they connect us to countless others who have endured suffering beyond their comprehension or control. This is my family’s historical context — a starting point for the purpose and meaning behind my life’s work in suicide prevention and healing across generations.

How has your family history shaped who you are today?

Learn More about PSALT-NK, a non-profit organization dedicated to increasing awareness of the crisis in North Korea and support the defectors through prayer, service, action, love, and truth.